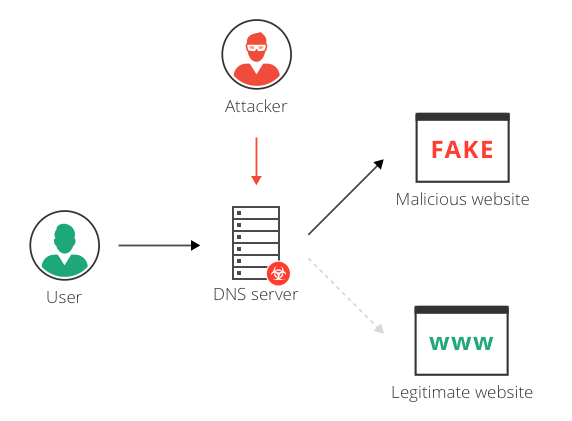

What is a DNS hijacking / redirection attack

Domain Name Server (DNS) hijacking, also named DNS redirection, is a type of DNS attack in which DNS queries are incorrectly resolved in order to unexpectedly redirect users to malicious sites. To perform the attack, perpetrators either install malware on user computers, take over routers, or intercept or hack DNS communication.

DNS hijacking can be used for pharming (in this context, attackers typically display unwanted ads to generate revenue) or for phishing (displaying fake versions of sites users access and stealing data or credentials).

Many Internet Service Providers (ISPs) also use a type of DNS hijacking, to take over a user’s DNS requests, collect statistics and return ads when users access an unknown domain. Some governments use DNS hijacking for censorship, redirecting users to government-authorized sites.

DNS hijacking attack types

There are four basic types of DNS redirection:

- Local DNS hijack — attackers install Trojan malware on a user’s computer, and change the local DNS settings to redirect the user to malicious sites.

- Router DNS hijack — many routers have default passwords or firmware vulnerabilities. Attackers can take over a router and overwrite DNS settings, affecting all users connected to that router.

- Man in the middle DNS attacks — attackers intercept communication between a user and a DNS server, and provide different destination IP addresses pointing to malicious sites.

- Rogue DNS Server — attackers can hack a DNS server, and change DNS records to redirect DNS requests to malicious sites.

Redirection vs. DNS spoofing attack

DNS spoofing is an attack in which traffic is redirected from a legitimate website such as www.google.com, to a malicious website such as google.attacker.com. DNS spoofing can be achieved by DNS redirection. For example, attackers can compromise a DNS server, and in this way “spoof” legitimate websites and redirect users to malicious ones.

Cache poisoning is another way to achieve DNS spoofing, without relying on DNS hijacking (physically taking over the DNS settings). DNS servers, routers and computers cache DNS records. Attackers can “poison” the DNS cache by inserting a forged DNS entry, containing an alternative IP destination for the same domain name. The DNS server resolves the domain to the spoofed website, until the cache is refreshed.

Methods of mitigation

Mitigation for name servers and resolvers

A DNS name server is a highly sensitive infrastructure which requires strong security measures, as it can be hijacked and used by hackers to mount DDoS attacks on others:

- Watch for resolvers on your network — unneeded DNS resolvers should be shut down. Legitimate resolvers should be placed behind a firewall with no access from outside the organization.

- Severely restrict access to a name server — both physical security, multi-factor access, firewall and network security measures should be used.

- Take measures against cache poisoning — use a random source port, randomize query ID, and randomize upper/lower case in domain names.

- Immediately patch known vulnerabilities — hackers actively search for vulnerable DNS servers.

- Separate authoritative name server from resolver — don’t run both on the same server, so a DDoS attack on either component won’t take down the other one.

- Restrict zone transfers — slave name servers can request a zone transfer, which is a partial copy of your DNS records. Zone records contain information that is valuable to attackers.

Mitigation for end users

End users can protect themselves against DNS hijacking by changing router passwords, installing antivirus, and using an encrypted VPN channel. If the user’s ISP is hijacking their DNS, they can use a free, alternative DNS service such as Google Public DNS, Google DNS over HTTPS, and Cisco OpenDNS.

Mitigation for site owners

Site owners who use a Domain Name Registrar can take steps to avoid DNS redirection of their DNS records:

- Secure access — use two-factor authentication when accessing the DNS registrar, to avoid compromise. If possible, define a whitelist of IP addresses that are allowed to access DNS settings.

- Client lock — check if your DNS registrar supports client lock (also known as change lock), which prevents changes to your DNS records without approval from a specific named individual.

- DNSSEC — use a DNS registrar that supports DNSSEC, and enable it. DNSSEC digitally signs DNS communication, making it more difficult (but not impossible) for hackers to intercept and spoof.

- Use Imperva’s Name Server Protection — a service providing a network of secure DNS proxies, based on Imperva’s global CDN. Each DNS zone receives alternative name server hostnames, so that all DNS queries are redirected to the Imperva network. The service will not only prevent DNS hijacking and poisoning, but also protect from distributed denial of service attacks (DDoS attacks) against your DNS infrastructure.