Based on a true story…

More than a couple of decades ago, I went to work for a network and web company as their customer marketing department. It was a crazy time. Online marketing was all about getting on DMOZ, Lycos was still a puppy, asking Jeeves felt like talking to an AI, and how you laid out your HTML tables had more of an impact on your search rankings than any inbound high PageRank link ever could. Google, shmoogle – it’ll never trump Dogpile. Back in those pre-bubble days, ring servers were all called Fodo, Bilbo, and Gandalf. Password1 (with a capital P) was pretty much de rigueur, and on-demand cloud computing was the stuff of William Gibson novels. For network, web dev, and IT support companies, it was like the wild west – and the digital frontier was open for business.

As I sat down at my new desk, I was told by one of my new colleagues, “Watch your feet; there’s a server under there. We’re not sure what’s on it. Ralf put it in before he moved to Canada.”

It was, if memory serves, an old 486 on its side. It could be the company mail server. It could be the print server. It could be backed-up client data. There could be a homemade firewall deployed on it. Maybe it was a dedicated monitoring server. Whatever it was, be careful and leave it on. It must be important after all, or why would Ralf have set it up?!

For two years, I sat there with that whirring box of RF radiation between my feet. Terrified of kicking it. Paranoid about unplugging it. Making sure it had enough ventilation to carry on doing whatever it was it was doing. All the time, my knowledge of such things was growing the more I wrote about networking and tech, and so one day – probably while rooting for a dropped Sharpie – my eyes fell on the back of this server. It was then I realized that, while there was an old-style Ethernet cable hanging out of it, this had taken a hit at some point and was dangling out of the socket on the wall, serving no purpose whatsoever.

I resolved to find out what was on the damn thing and dragged it (with its warren of dust bunnies) out into the daylight. Plugging a monitor and a keyboard in, and a mere 10 minutes later, I discovered the truth. Ralf had set up a LAN for after-work gaming, and this was the dedicated Doom server. For three years, this thing had been plugged in, sucking up Watts, slowly cooking my ankles, doing basically nothing.

The more things change, the more they stay the same

In many ways, little has changed. When telling a friend this story, she told me that the previous year she’d found a copy of ‘The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’ interactive text-based adventure game (by Infocom, circa 1984) on a drive of legacy warehouse data that had been blindly copied across and copied across for decades.

If only it were all as innocent as outdated computer games. Organizations are storing masses of unknown, untapped, unstructured data, across structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data stores, locally and in the cloud. Much of this is dark data. It’s a waste of space, resources, and energy, often in contravention of local data laws, and manual triage is almost impossible. From old server log files and outdated accounts data to long-forgotten shipping information and decades of emails, business data repositories are filled with the day-to-day byproducts of our ongoing digital interactions.

Some of this may actually be valuable. It may be able to help organizations make more educated business decisions by analyzing the data of the past, or it may just be taking up space they are paying for with no further application whatsoever.

According to the research firm IDC, the volume of unstructured data will grow to 175 zettabytes, by 2025. A high percentage of this will undoubtedly be the modern-day equivalent of Ralf’s Doom server.

A call for discovery and classification

It’s a time-consuming and laborious process to find out what unstructured data an organization has. GDPR (and other standards) means that organizations must maintain a complete inventory of personal data, and then classify that data. Without insight into that data, this is impossible.

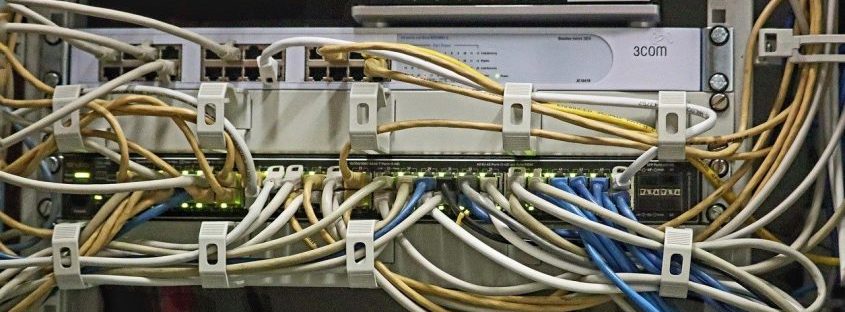

IT and security teams need to identify all their data sources, evaluate their current technology stack – including servers like Ralf’s, gain real-time access, leverage data lakes, clean the data, then recover it, categorize it, classify it, compartmentalize it, and segment it for future use. This is no small feat, but at some point, it will need to be done – and sooner rather than later is going to be the best policy. Doing this manually is the stuff of nightmares, but organizations need to know (and have visibility into) the location, volume, and context of structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data stored across all their data repositories.

We have a solution for this. Imperva Data Security Fabric Discover and Classify (DSFDAC) lets busy security teams do this straight out of the box and at an enterprise scale. Powered by machine learning, it scans business networks to reveal where databases are located and what type of information they hold. DSFDAC allows organizations to find sensitive, hidden, and exposed data and then protect it before it’s found by bad actors and auditors. It offers clear and actionable suggestions for compliance and categorization. It builds and maintains a detailed, real-time inventory of data across an organization and can create automated, scheduled scans to identify any sensitive business data. I wish we’d had that back in the ‘90s.

Thank you, Ralf, wherever you are. You taught me a valuable lesson and one I won’t forget. It makes me wonder just how much of the unexplored data out there is another Ralf’s Server, how much has a legal protection requirement, and how much actually has a genuine business value.

Try Imperva for Free

Protect your business for 30 days on Imperva.